(Click picture to enlarge)

River cruise boats on the Daugava river, south of Old Town RÄ«ga. Photo taken by me, August 2015.

In this series, I am providing pictures of tombstones from Latvian cemeteries, all with death dates prior to 1945. I do not have any further information on the people mentioned.

Photo taken by me, December 2014. Click to enlarge.

Names: Roberts Bahmanis, born 1852, died 1909; Heinrihs Mullers, born 1879, died 1915.

Bottom Inscription: Jer. 31:3

Location: Sloka Lutheran Cemetery, Sloka

Latvia is not and has never been one monoethnic entity. Certainly, Latvians – and Luteran Latvians, at that – have made up the majority, but they are not the only ones living in Latvia. Throughout the years, there have been many different ethnicities and religions living here, sometimes spread out, and sometimes in enclaves.

These historical enclaves are what I will be writing about today – I say “historical”, because for the most part, they either no longer exist, or they are no longer exclusive enclaves.

Let’s start with a religious enclave – the Suiti of western Kurzeme, near the Baltic Sea coast between LiepÄja and Ventspils. The Suiti are Latvians, but instead of being Lutherans, as was the norm in Kurzeme, they are Catholics. While Kurzeme did become Protestant during the Protestant Reformation, this changed in the mid-1600s, when the son of the local baron married into Polish nobility, which required him to become Catholic. And so it was that all of the estates he owned – AlÅ¡vanga, Adze, Basi, Deksne, DÅ«re, Feliksberga, GrÄveri, Gudenieki and hen later on also Birži and AlmÄle, also had to convert to Catholicism. The ensuing isolation in what was otherwise a sea of Protestantism meant that they preserved aspects of Latvian culture that changed in other parts of the country, including a unique dialect and traditional clothing. The Suiti still exist today and are even listed by UNESCO in the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Another religious (and ethnic) enclave in western Latvia was that of Old Believers in Virbi, between Talsi and Sabile. Old Believers are a group that split off from the Russian Orthodox church in the 17th century after Patriarch Nikon instituted a number of reforms. They did not accept these reforms, were branded schismatics and persecuted in Russia. Many took refuge in Latvian territories – which did eventually come under the auspices of the Russian Empire, but since most control was still in the hands of German barons, it does not appear that they suffered further persecution at this time. In fact, this group of Old Believers in Virbi came about in 1908, when agricultural reforms meant that land was bought by the government and sold to people without land – which in this case ended up being a large group of Old Believers. What happened to the Latvians living in the area? I don’t know and would need to investigate this further, since I don’t believe that the Old Believers were there prior to that – from the sounds of it, they came with the railway that was finished at that time between RÄ«ga and Ventspils. The Old Believers consecrated their church, the Neivekene Old Believers’ Church, in 1928. However, by 1990, the community no longer existed, and the church fell into disrepair and was torn down.

The third enclave I am going to mention today is an ethnic enclave – the German colony of IrÅ¡i (Hirschenhof in German), in central Latvia. This German colony came about in the 18th century when Catherine the Great invited German farmers to move to the Russian Empire. They would be free peasants subject directly to the crown. They were guaranteed religious freedom, their own government and representatives, as well as the right to rent taverns. For awhile they were even exempt from taxes and military service. The local Latvian serfs were dispersed to other nearby estates. Eventually people started emigrating from the colony to cities around the Baltic provinces, but until 1939, the area was still predominantly German. In 1939, however, most repatriated to Germany and no Germans live there today.

Are your family’s ancestors from one of these enclaves? Or did they live nearby and know the people who lived there? Share their stories in comments!

New format of Surname Saturday here on Discovering Latvian Roots – if you want surname meanings, go check out the Facebook and Twitter pages, here on the blog it will be a summary of what’s new on the Latvian Surname Project, as funded by my supporters on Patreon!

New this week!

Parishes added – AknÄ«ste, Jaunsaule, NaudÄ«te, Prauliena

Names added – Ciemiņš, GriÅ¡onoks, Petrovskis

… and over 35 other names have been updated to reflect their presence in more parishes!

The Surname Project currently includes 1337 surnames from 482 parishes, towns and cities. Many parishes only have a few names listed so far, but I’m working every day to add more for each parish!

Seventy-fifth installment from the diary of my great-grandfather’s sister Alise, written during the First World War. When the diary starts, she is living just a few miles from the front lines of the Eastern Front, and is then forced to flee with her husband and two young daughters to her family’s house near Limbaži as the war moves even closer. Her third child, a son, was born there in February 1916. The family has now relocated (again) to a home near Valmiera, and the Russian Revolution is in full swing. For more background, see here, and click on the tag “diary entries†to see all of the entries that I have posted.

If there is mention of a recognizable historical figure and event, I will provide a Wikipedia link so that you can read more about the events that Alise is describing. It is with this entry here that the calendar in Latvia changed from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar.

August 15, 1918 (July 31 Old Style)

People are confused… some are celebrating festivities and birthdays by the old calendar, others by the new, others both, however they wish. Oh, what times we live in! Instead of real tea, now we are preparing apple leaves, which we boil and then dry in the oven. Instead of tobacco, now they use dried raspberry leaves, whose smoke is quite similar to tobacco. It already feels like fall, looking at the plowed rye heaps. Thank God, we have prevented famine. The song of the young rooster brings us closer to fall storms.

Are you considering giving the gift of family history this Christmas (or other winter holiday)?

If you are, don’t wait until the last minute! Especially if you want the sights of summer included!

If you head over to my Services page, you will see a new addition to the research services family – I have a special Starter/Gift Package on offer. This package is ideal as a holiday gift for a loved one, or as a starter package that can lead to more research later on.

For $299, you will receive 8 hours of research, a GEDCOM (genealogy standard computer file) with all of the family information, photocopies of documents found and a photoset of pictures from one of your ancestral locations – anywhere in Latvia! That’s right – I will go out to the village or parish of your ancestors, take photos of the church, main village centre and other important locations. If there’s a local cemetery, I can also take a peek in there for any family members. All of this is included – no extra fees involved!

If this is something that interests you, don’t delay! All the details and contact information are on my Services page. Summer is coming to an end soon, so if you want summertime photos, they will need to be done soon!

This is the third post in a series about Finnic influences in Latvia. You can read the first one about place names here and the second one about personal names here.

Today we will be looking at population crossover. But I really wonder whether “crossover” is the right word, because for most of history, a border between Latvia and Estonia did not exist. Border controls have only existed along the Latvian-Estonian border for no more than 50 years in the past seven centuries – and those have all been in the 20th century. Firstly, during the interwar period, when Latvia and Estonia were both independent countries, and secondly, after regaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, until 2007 when both countries joined the Schengen area, so practically speaking, the border doesn’t exist anymore.

As I’ve mentioned before, prior to the independence in 1918, northern Latvia and southern Estonia were one province in the Russian Empire – Livland. This public domain map from Wikipedia shows the reach of Livland. I have added in a rough approximation of the modern modern between Latvia and Estonia in red. You can click on it to get a bigger version.

Now, this modern border comes close to following the borders of the different districts in the Livland Empire – Parnu, Viljandi and Võru districts to the north of the border, Valmiera and Valka districts to the south of it. There are some variations, and these came about in the years following the First World War. A series of local votes took place in a variety of places, including Ainaži, to determine whether a place would become part of Latvia or part of Estonia. In the case of Ainaži, the vote went in Latvia’s favour, in the case of the island of Ruhnu in the Gulf of RÄ«ga, the vote went to Estonia. The town of Valka (Valga in Estonian) was divided between the two countries, with most of the town going to Estonia.

But back to the populations themselves. The linguistic border was there, but since landless peasants often had to travel where the work was, and the manor lords on both sides of the linguistic border spoke German, traveling across the linguistic border was not as hard as it could be. Some churches in the border regions even had three congregations – the Latvian, Estonian and German.

Typical Latvian names like Kalniņš, KrÅ«miņš and Ozols appear on the Estonian side of the linguistic border, while Estonian names such as Jurikas, Pottisepp and Tamm appear on the Latvian side. As well, since revision lists don’t mention ethnicity, there could be even more crossovers who are hidden behind Germanic names, since these surnames were common for both Latvians and Estonians.

Beyond travel between rural manorial estates, people also traveled extensively for urban work or study purposes – Latvians headed into Estonian territory to study at the University of Tartu, and Estonians migrated to RÄ«ga in Latvian territory to study at the RÄ«ga Polytechnic Institute, as well as work in factories, since RÄ«ga was a large industrial centre. The Estonian student corporation Vironia was founded at the RÄ«ga Polytechnic Institute in 1900, while the Latvian student corporation Lettonia was founded at the University of Tartu in 1870. Prior to independence, about 28,000 Estonians lived in RÄ«ga. Many assimilated to either Latvian or Russian cultures. However, some Estonians did maintain their identity. After the First World War and the establishment of Latvian and Estonian independence, thousands of Estonians still called Latvia home. About 1600 lived in RÄ«ga, where their social life revolved around the Estonian school and community centre in the Ä€genskalns neighbourhood. RÄ«ga still has an Estonian school today, and is attended not only by Estonians but ethnic Latvians as well, where they get to learn the Estonian language.

An important thing to note, if you are researching Estonian Latvians – many of them – though not all – were a part of the Orthodox religion. especially in RÄ«ga, where they had their own Estonian congregation. While Orthodoxy did make some inroads among Latvians in the 19th century – particularly in central Latvia around Madona – it was still not as popular as Lutheranism. Meanwhile, about 20% of Estonians were of the Orthodox religion. It was especially popular on the island of Saaremaa – which, as you can see on the map above, was a part of the province of Livland, and contributed a number of migrants to Latvian territory. An exception to the traditional Lutheran and Orthodox Estonians would be a Catholic “island” of Estonians in Latvia – the “Lutsi”, a group of Estonian Catholics who lived around Ludza in eastern Latvia.

Next time, we have the last post in this series – Finnic influences on the Latvian language. With Latvian being Baltic and Estonian being Finnic, you wouldn’t think there is much crossover or borrowing – but there is! Stay tuned!

This post is made possible by my supporters on Patreon. Sign up there to support my work and be the first to know about my new projects and products!

In this series, I am providing pictures of tombstones from Latvian cemeteries, all with death dates prior to 1945. I do not have any further information on the people mentioned.

Photo taken by me, October 2014. Click to enlarge.

Name: Anna Dumpe, nee Zviedris, born December 6, 1906, died October 31, 1927

Bottom Inscription: “AcÄ«m tÄļu, tÄļu, Sirdij mūžam tuvu, Dusi saldi” (Far, far from our eyes, but always close in our heart, rest in peace)

Location: PÄ“terupes kapi, PÄ“terupe, Saulkrasti

One common point of confusion/frustration when it comes to tracking Latvian locations on maps throughout the centuries is the big jumble of administrative divisions. Some have stayed constant and relatively simple – like cities, albeit increasing in size – while smaller rural places have undergone a lot of changes.

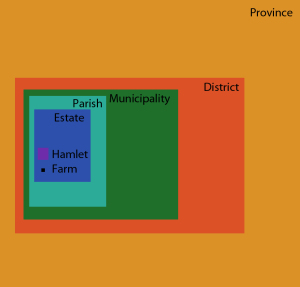

To make this process easier, I’ve made this simple graphic illustrating relative sizes of the different administrative divisions. You can click the image to enlarge it if you want to.

The smallest unit of adminstrative division is the individual farm (viensÄ“ta) – unlike rural administration in places like North America, where rural properties might have a name, but are officially known by a number, be it a street number or a block number or quadrant number, in Latvia they have always been known by their names. Some farm names are centuries old, others are new. Yet more are modifications on original names.

The next unit is one found in Latgale (eastern Latvia), as well as some neighbouring areas in Zemgale and Vidzeme, and that is the hamlet (sÄdža). This is a cluster of houses, with the farmland on the outside of the house cluster. Sometimes, when surnames were assigned (be it in the 1860s or earlier, since many places in Latgale did have surnames before the official need for them), the entire hamlet would get the same surname, regardless of the relationship between the different families. In the interwar independence period, these hamlets were subdivided into individual family farms, but often the hamlet name still remained.

The next level of division – and the first formal administrative level – is the manorial estate (muiža). These estates were owned and administered by the upper classes, usually German, but sometimes Polish or Russian, especially in Latgale. Farms and hamlets were part of these estates, and provided taxes and unpaid labour to them. During serfdom, the serfs were tied to farms on a particular estate, and were not free to leave. The manor lords were responsible for local administration of the peasants, which sometimes included corporal punishment for infractions. If a piece of land was sold to a different owner, the serfs would also be transferred to them. After serfdom was abolished, people were able to move around more, but still not very freely (but thankfully, meticulous records of these movements were kept, and many of these records survive, which is a real boon for researchers! Read more in this post). When it was possible to buy farms from the manor lords, the new land owners still had to provide all sorts of services and rights to the owners of the estates that they purchased their land from. Unlike the hamlets mentioned above, in the estate system with individual farms, care was taken to not duplicate surnames, meaning typically only one family had a surname on an estate.

The next level up is the parish (pagasts) – while parishes frequently correspond to the boundaries of a large estate, they can also include a number of smaller estates. Parishes were established after serfdom was abolished, and they began to administer local matters, such as taxes, road repair and care for the poor and elderly. Power in the parish councils ostensibly belonged to the peasants, but the manor lords still exerted a lot of influence on the local communities until the independence era and the abolition of the estates. Parishes also exist today, though their influence is reduced, with the creation of another level of administration – the “novads”.

How to explain the novads? I’m not even sure. I will call it a municipality in English. The municipality is an administrative division smaller than the district (apriņķis) division of old – but bigger than a parish (usually, there are some municipalities that are the size of one parish, which makes me wonder what the point is). Furthermore, some of these municipalities include towns as well as their “rural territory”.

Besides the parishes and municipalities, there are the cities of the Republic (Republikas pilsÄ“tas) – some of them also have a municipality, but the city is administrated separately, subject only to the government of the Republic of Latvia. There are nine cities in this category: Daugavpils, JÄ“kabpils, Jelgava, JÅ«rmala, LiepÄja, RÄ“zekne, RÄ«ga, Valmiera and Ventspils.

Prior to the municipalities, there were the districts (apriņķi) mentioned above – nineteen in all in the interwar era, and many of them existed prior to that as well. These districts managed police, military recruitment and other facets of life. This is especially important for finding records in areas where parish records might not survive – chances are at least some of the district-level records still do!

Then there are the provinces – however, in independent Latvia, they are considered simply cultural regions, and do not have any sort of administrative capacity. There are four of them historically speaking – Kurzeme, Vidzeme, Latgale and Zemgale, but today there is often a fifth one included as a separate cultural region, and that is Selija, the eastern part of Zemgale, which has closer cultural ties with Lithuania than other parts of Latvia, and occupies a sort of middle ground between Latgale and the other provinces – this area has a lot of hamlets instead of individual farms, and a large proportion of residents are Catholic, but Lutherans are still mostly dominant. Prior to independence, there were three Baltic provinces of the Russian Empire, encompassing most of Latvian territory, as well as all of Estonia. The Baltic provinces consisted of Estland (northern Estonia), Livland (southern Estonia and the Latvian province of Vidzeme) and Kurland (the Latvian provinces of Kurzeme and Zemgale). Lithuania was not a part of the Baltic provinces, nor was Latgale, which was instead a part of the Vitebsk province of the Russian Empire. In the Russian Empire, these provinces did have all sorts of administrative powers (and consequently, also another level of records).

I hope this helps dispel some of the confusion! Administrative divisions aren’t easy at the best of times in countries that haven’t had a lot of wars and different foreign occupations – which means that for a country like Latvia that has, it can be a real challenge!