One common point of confusion/frustration when it comes to tracking Latvian locations on maps throughout the centuries is the big jumble of administrative divisions. Some have stayed constant and relatively simple – like cities, albeit increasing in size – while smaller rural places have undergone a lot of changes.

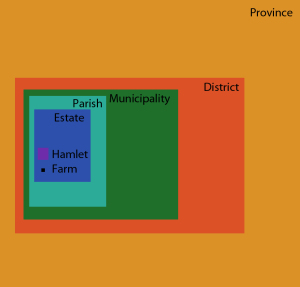

To make this process easier, I’ve made this simple graphic illustrating relative sizes of the different administrative divisions. You can click the image to enlarge it if you want to.

The smallest unit of adminstrative division is the individual farm (viensÄ“ta) – unlike rural administration in places like North America, where rural properties might have a name, but are officially known by a number, be it a street number or a block number or quadrant number, in Latvia they have always been known by their names. Some farm names are centuries old, others are new. Yet more are modifications on original names.

The next unit is one found in Latgale (eastern Latvia), as well as some neighbouring areas in Zemgale and Vidzeme, and that is the hamlet (sÄdža). This is a cluster of houses, with the farmland on the outside of the house cluster. Sometimes, when surnames were assigned (be it in the 1860s or earlier, since many places in Latgale did have surnames before the official need for them), the entire hamlet would get the same surname, regardless of the relationship between the different families. In the interwar independence period, these hamlets were subdivided into individual family farms, but often the hamlet name still remained.

The next level of division – and the first formal administrative level – is the manorial estate (muiža). These estates were owned and administered by the upper classes, usually German, but sometimes Polish or Russian, especially in Latgale. Farms and hamlets were part of these estates, and provided taxes and unpaid labour to them. During serfdom, the serfs were tied to farms on a particular estate, and were not free to leave. The manor lords were responsible for local administration of the peasants, which sometimes included corporal punishment for infractions. If a piece of land was sold to a different owner, the serfs would also be transferred to them. After serfdom was abolished, people were able to move around more, but still not very freely (but thankfully, meticulous records of these movements were kept, and many of these records survive, which is a real boon for researchers! Read more in this post). When it was possible to buy farms from the manor lords, the new land owners still had to provide all sorts of services and rights to the owners of the estates that they purchased their land from. Unlike the hamlets mentioned above, in the estate system with individual farms, care was taken to not duplicate surnames, meaning typically only one family had a surname on an estate.

The next level up is the parish (pagasts) – while parishes frequently correspond to the boundaries of a large estate, they can also include a number of smaller estates. Parishes were established after serfdom was abolished, and they began to administer local matters, such as taxes, road repair and care for the poor and elderly. Power in the parish councils ostensibly belonged to the peasants, but the manor lords still exerted a lot of influence on the local communities until the independence era and the abolition of the estates. Parishes also exist today, though their influence is reduced, with the creation of another level of administration – the “novads”.

How to explain the novads? I’m not even sure. I will call it a municipality in English. The municipality is an administrative division smaller than the district (apriņķis) division of old – but bigger than a parish (usually, there are some municipalities that are the size of one parish, which makes me wonder what the point is). Furthermore, some of these municipalities include towns as well as their “rural territory”.

Besides the parishes and municipalities, there are the cities of the Republic (Republikas pilsÄ“tas) – some of them also have a municipality, but the city is administrated separately, subject only to the government of the Republic of Latvia. There are nine cities in this category: Daugavpils, JÄ“kabpils, Jelgava, JÅ«rmala, LiepÄja, RÄ“zekne, RÄ«ga, Valmiera and Ventspils.

Prior to the municipalities, there were the districts (apriņķi) mentioned above – nineteen in all in the interwar era, and many of them existed prior to that as well. These districts managed police, military recruitment and other facets of life. This is especially important for finding records in areas where parish records might not survive – chances are at least some of the district-level records still do!

Then there are the provinces – however, in independent Latvia, they are considered simply cultural regions, and do not have any sort of administrative capacity. There are four of them historically speaking – Kurzeme, Vidzeme, Latgale and Zemgale, but today there is often a fifth one included as a separate cultural region, and that is Selija, the eastern part of Zemgale, which has closer cultural ties with Lithuania than other parts of Latvia, and occupies a sort of middle ground between Latgale and the other provinces – this area has a lot of hamlets instead of individual farms, and a large proportion of residents are Catholic, but Lutherans are still mostly dominant. Prior to independence, there were three Baltic provinces of the Russian Empire, encompassing most of Latvian territory, as well as all of Estonia. The Baltic provinces consisted of Estland (northern Estonia), Livland (southern Estonia and the Latvian province of Vidzeme) and Kurland (the Latvian provinces of Kurzeme and Zemgale). Lithuania was not a part of the Baltic provinces, nor was Latgale, which was instead a part of the Vitebsk province of the Russian Empire. In the Russian Empire, these provinces did have all sorts of administrative powers (and consequently, also another level of records).

I hope this helps dispel some of the confusion! Administrative divisions aren’t easy at the best of times in countries that haven’t had a lot of wars and different foreign occupations – which means that for a country like Latvia that has, it can be a real challenge!